Crip Camp

THE DISABILITY RIGHTS MOVEMENT WAS BORN AT A CAMP RUN BY HIPPIES.

I’m very tired of being thankful for accessible toilets. If I have to be thankful for an accessible bathroom, when am I ever gonna be equal in the community?

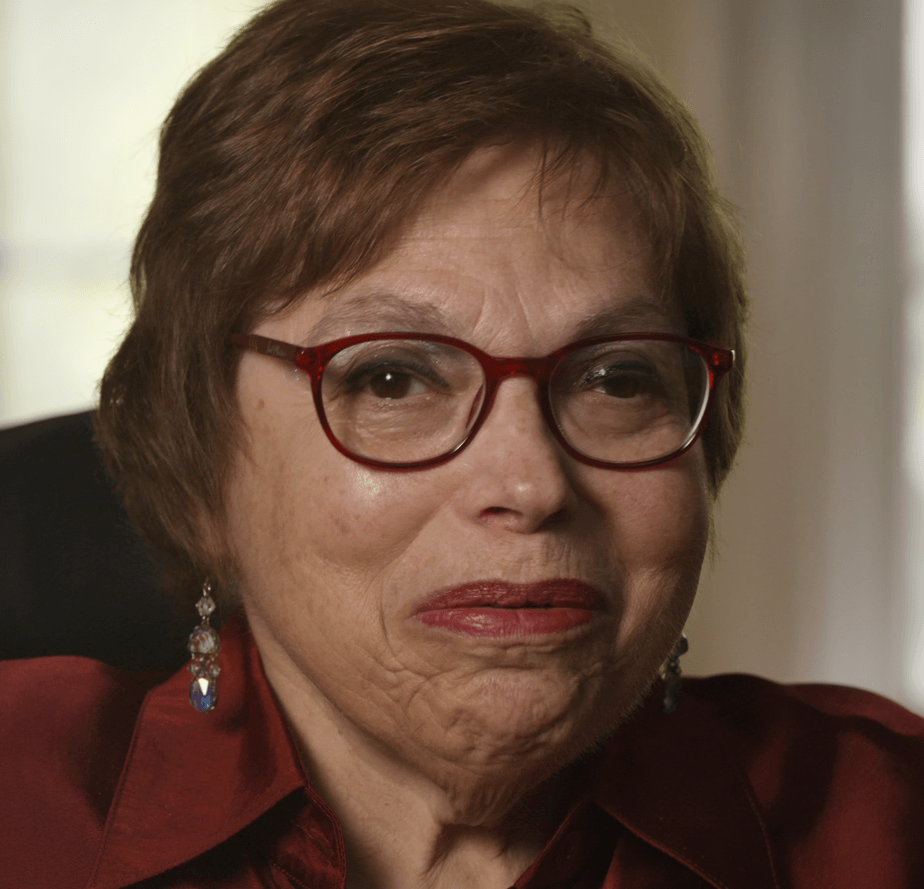

When Judy Heumann poignantly asks that question in the 2020 Academy Award-nominated documentary Crip Camp, the camera lingers on Heumann’s face. The directors didn’t hurry, but instead chose to give viewers time for Heumann’s words to sink in. Because even in a documentary recounting how far we’ve come, directors Nicole Newnham and James LeBrecht know there’s still work left to do.

Camp Jened itself was a pivotal moment for the disability rights movement because that community, where campers could finally participate without barriers, inspired many of them to fight for a society with fewer barriers—a world that looked more like Camp Jened.

A LIFE-CHANGING EXPERIENCE

The film, which also garnered a 2021 Peabody Award, spans five decades, beginning in 1971 at Camp Jened, a summer camp in the Catskills for disabled people.

“I knew there was a story here that was going to be lost to time if it didn’t get told,” says LeBrecht, who has been a sound mixer for documentaries for more than two decades. “There were two factors in wanting to make the film: not seeing [a] documentary that would hopefully speak to the disability experience through the lens of people with

that lived experience and trying to reframe what disability means for people with and without them. [Camp Jened was] this incredible experience that captured that.”

LeBrecht understood that the power of Camp Jened, an accessible space designed for disabled kids, teens and adults to just be themselves, went beyond the imagery of campers playing baseball or participating in the usual summer camp activities. Camp Jened itself was a pivotal moment for the disability rights movement because that community, where campers could finally participate without barriers, inspired many of them to fight for a society with fewer barriers—a world that looked more like Camp Jened.

Personally, LeBrecht says, Camp Jened challenged how he had allowed public perception of disability and disabled people to shape how he viewed himself. “

Getting the sense that people [at Camp Jened] were proud of who they were and that disability was nothing to be ashamed of was life-changing,” LeBrecht says. He had never experienced that anywhere else.

TRACING THE CAMP JENED EFFECT

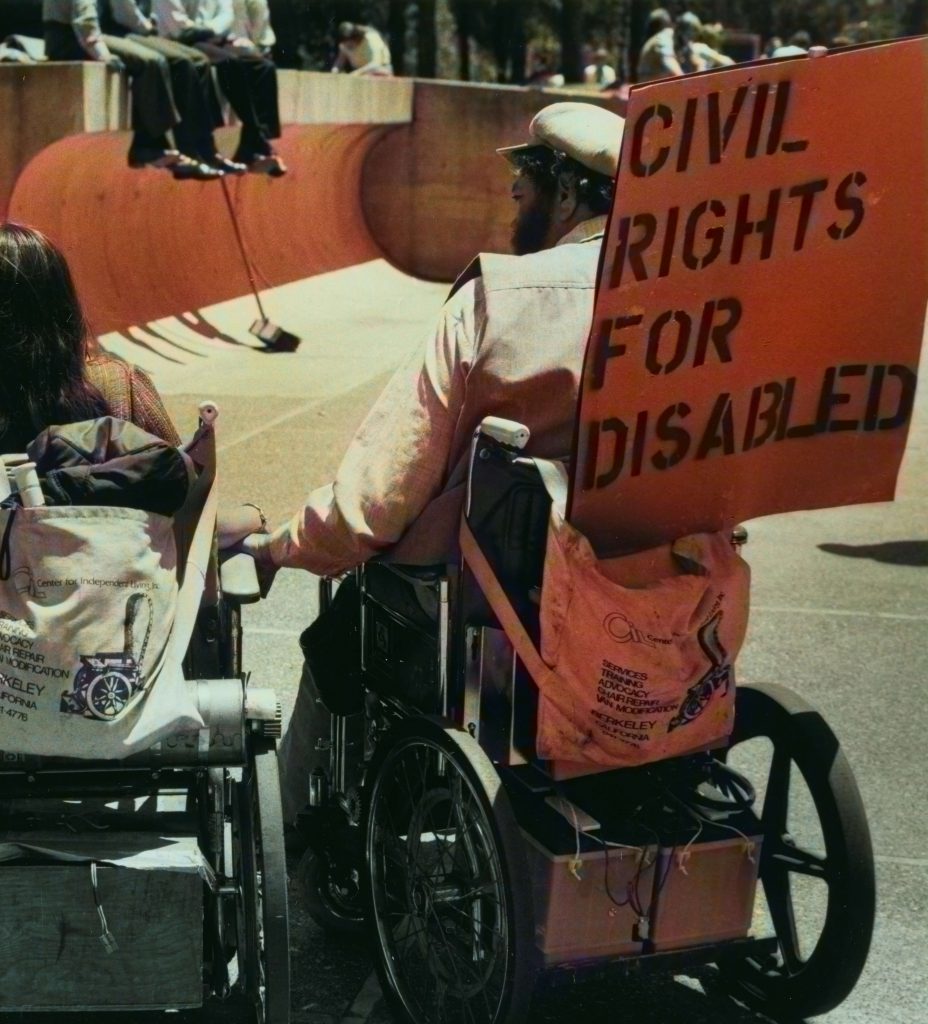

In the 1970s, LeBrecht recalls, many disabled people began to move from New York to Berkeley, California, “recreating our community that we found in camp but in much better circumstances.” Many former Jened campers, living in Berkeley and across the country such as Heumann, Bobbi Linn, and LeBrecht became disability activists. Jenedians, as former campers are also called, were heavily involved in the 1977 Section 504 sit-in in San Francisco, which LeBrecht calls “a very important story for our community.”

“It still to this day is the longest non-violent takeover of a federal office,” says LeBrecht. “We were really fighting to get some kind of civil rights protection.”

That 28-day sit-in is detailed in the documentary. Part of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504 prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities in programs or services that receive federal funding—but regulations defining what that meant had been delayed for years. Scholars and disability activists alike widely recognize Section 504 as a necessary precursor to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

The Camp Jened experience also shaped other aspects of the disability rights movement. According to prominent disability rights activist Heumann, a former Jened camper and staffer, the 1970s reflected an “emerging disability rights movement,” but the work wasn’t centralized. While numerous organizations and groups focused on specific types of disabilities, few were working together.

The lessons Heumann and others had learned at Camp Jened challenged that mindset.

We were really fighting to get some kind of civil rights protection.

“Camp Jened was cross-disability in a number of interesting ways,” Heumann recalls. “At that point, for two summers, there were three Deaf teenagers who were in my bunk. That was the first time I’d ever met any Deaf people.”

Heumann’s fellow campers began teaching her American Sign Language, even though the camp’s speech therapist

warned it would discourage deaf campers from learning to read lips. Moments like these, Heumann recalls, taught the Jenedians about the vitality of crossdisability rights.

THE PATH FORWARD

LeBrecht and Heumann both believe that we have come a long way since 1971, thanks largely to representation in the media as well as legislation that makes it possible for disabled people to access the world with fewer barriers.

But there’s still a lot of work to be done.

“Things have changed a little, but the reality is that the average person is seeing disabled people more than before because of all these laws that we’ve been discussing,” says Heumann. “As disabled people, we see ourselves reflected more than in the past. But we’re still pretty absent.”

LeBrecht agrees, stressing the importance of opening doors across the entertainment and media industries to disabled people, including journalists, television writers, producers, filmmakers and more.

“If the media doesn’t change and employment doesn’t improve within the entertainment business, the stories are going to continue being the old tropes of tragedy or overcoming adversity,” he explains. “I think Crip Camp has really helped to show the entertainment industry that there are unique, unknown, and compelling stories within the disability community. People with disabilities are just as creative and capable as anyone else to create and produce these films and television shows.”

Access barriers weren’t completely erased by the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Air travel is still a major concern, especially for wheelchair users. Research shows that before the decrease in travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic, airlines reported 29 damaged, lost, delayed, or stolen wheelchairs on average per day. Additionally, the low asset and saving limits of Supplemental Security Income for disabled people forces individuals to stay in poverty.

Heumann believes that the keys to change are collaboration and cooperation. It’s critical, she says, for disabled people from different industries to meet each other and connect.

LeBrecht agrees, stressing that networking opportunities and social events need to be accessible, because these are often the places where real community is built and as a result, change happens. “If my way of getting into the industry is a) being able to attend networking events and b) being able to lift that box of 20-pound printer paper, you’re filtering out a whole bunch of people who could be incredible talent on your crew,” he says. “Networking events need to be accessible.”

The work is moving forward. Organizations such as FWD-DOC, 1in4 Coalition, and Disability Media Alliance Project are creating change for disabled people in the entertainment industry. Netflix really stepped up in terms of accessibility for Crip Camp, LeBrecht says, by offering audio description in more languages than they ever had before, captioning in more languages, and providing the option to download the transcript of the film, for Braille readers, a suggestion from Haben Girma.

These are all positive steps forward, LeBrecht says, but he hopes they point to a change in peoples’ hearts rather than additional legislation.

“You can pass a law but as long as you don’t change society’s view, it’s not going to do a lot,” LeBrecht says, quoting Denise Sherer Jacobson’s words from the documentary.

More Stories

Related Articles

A Day in My Life: Calvan Ferguson

Calvan Ferguson shares about his daily life, the importance of inclusion and accessible transportation and cultivating a positive attitude. Calvan Ferguson believes deeply in the…

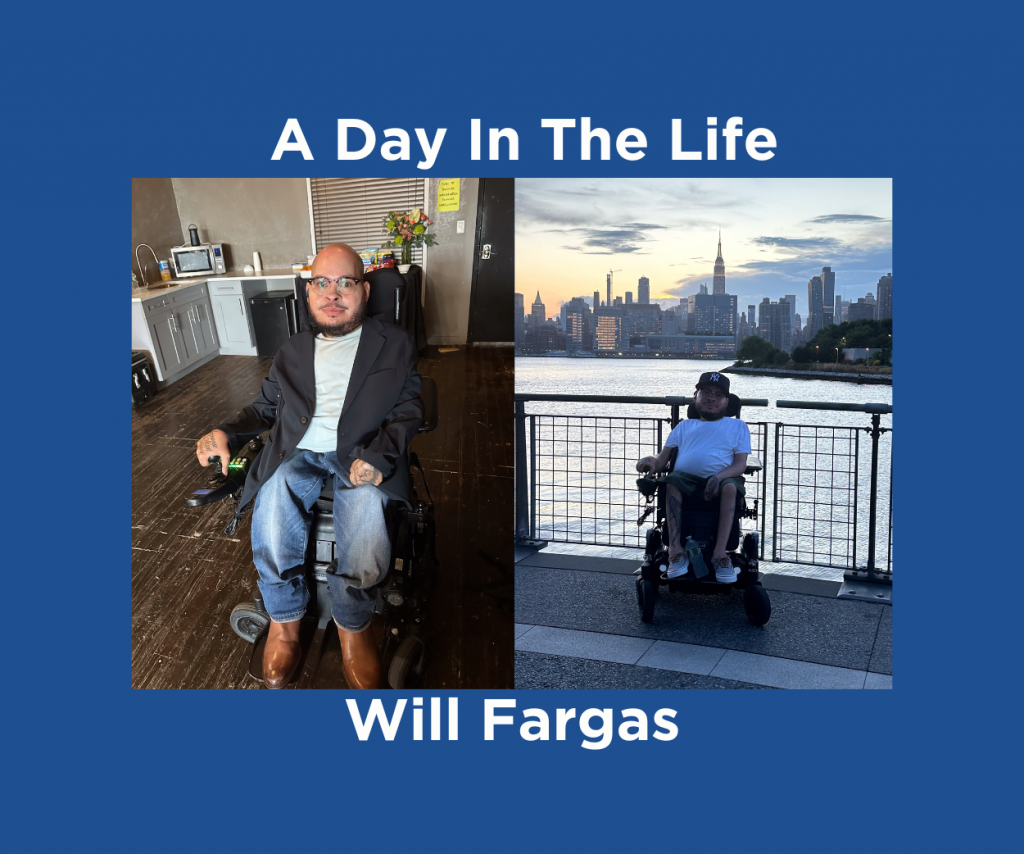

A Day In My Life: Will Fargas

NSM client Will Fargas takes us along for the day as he heads to work in Manhattan For Will Fargas, most days start pretty early. …

Game Changers

National Seating and Mobility clients and athletes discuss sports, active living and keeping their chairs competition-ready. Sports can be an important part of living an active,…